Where to Begin? Refugees in Lesvos… Day Three.

- erinschrode

- Oct 27, 2015

- 10 min read

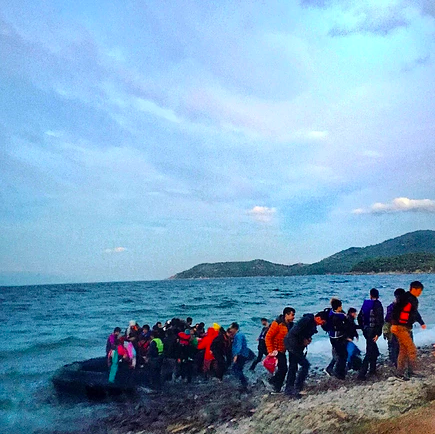

I don’t even know where to begin. How can I describe in words what has happened in the past few hours? The refugee crisis here on Lesvos is beyond comprehension – and we witnessed the brunt of it with three harrowing night rescues tonight, after a day of full on Robin Hood-ing about the island.

Our morning drive once again yielded panoramic views of the bright orange coastline; the stacks of discarded life jackets are evidence that this picturesque Greek island has received 300,000 refugees this year alone. Each one represents a human being, a survivor, a dreamer – and I am here to witness, embrace, assist, and share.

After waiting to have our car battery replaced (a long story that is not worth my breath), we raided the warehouse (hence the Robin Hood reference) and packed our car full of dry clothes, socks and shoes galore, mostly for babies and children. While making our way along the shoddy dirt ditch-ridden road to the transit camp on the northern coast, we spotted four boats dotting the horizon line. The Turkish landmass from where dinghies depart is as short as six kilometers away, so in theory, it should be a quick trip, though with overcrowded shoddy boats, unpredictable winds and currents, and no captain in sight (the smugglers appoint one person as such prior to send off, who is given a discount, though receives no training whatsoever), the journey often takes three or more hours, with one boat at sea for over twelve hours yesterday, before its coast guard rescue. We turned onto a rocky beach road, making our way toward where one boat seemed to be headed. We arrived to a mass of people huddled together, shaking and crying, no authority or volunteer or aid worker to be seen – only a Greek fisherman, cutting panels out of the boat (probably, to fix his own) and stealing (yes, stealing) the motor, a frequent occurrence, though one which the police recently said they will try to crack down on. We beckoned the women and children to our car, mixing and matching colorful, dry outfits and shoes for all. Jodi dressed one little girl in pink and yellow from head-to-toe, complete with a crocheted hat, iridescent raincoat, cotton leggings, you name it. Her father asked for a photo with me, which his eldest son wanted to join, and then his little boy came barreling over from across the beach, as to not miss his chance to star in our ‘family’ portrait. It was an adorable, jubilant moment – and then harsh reality set in, when I inquired as to where he came from. “Syria.” “Why did you leave?” I probed, sincerely wishing to know his personal answer. “Da'ish,” he said, crossing his hands and flicking his wrists as if to gesture 'end of story.’ Da’ish is the Arabic acronym for ISIS. Da'ish is the reason that millions are fleeing their home countries of Iraq and Syria (the I and S in the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria). Da’ish is terrorizing its people and directly responsible for immeasurable and untamed destruction. It was clear that he did not wish to speak on the subject any further, asking me what came next in their journey. I shuttered. “You must walk up that hill,” I explained, pointing to a daunting mountain, "and continue onwards to Eftalou, where a bus will meet you to take you to camp.” I sincerely hoped the buses were running with more frequency and less chaos than yesterday. “How long?” his question was frank. “Honestly, an hour and a half, maybe longer.” I heard other volunteers lie, claiming people could cover great distances in implausibly short lengths of time (particularly considering heat, heavy possessions, children, elderly, and exhaustion), but I broke the bad news out front – all the while wishing that I could take every last one of them in my car at that very second or implement efficient modes of transportation (or supernatural winged carriers!) for all who washed up on these shores. These brave souls were not daunted by the relatively tame walk ahead, having already been traveling for days through conditions I cannot imagine, also aware that months of unknown dangers and physically taxing journeys lie ahead. Off they went – with bright spirits, hungry stomachs, dry clothes, and soaked possessions.

Driving on, we encountered a man and his son in sopping wet clothing and no shoes, with miles more to walk. We pulled over to offer help, which they accepted with literal open arms. I helped Farad into cozy warm kiddie attire, before rebundling the shivering tot in his emergency blanket and sizing their feet to find two perfect pairs of sneakers; the ones they began their journeys with in Afghanistan had been lost at sea, like so many possessions. Albeit a small small victory, our mission was complete – or almost.

We packed the father-son duo, his very pregnant sister, her husband, and their two children into our uber compact car to shuttle them to the nearest camp. Our drive was interrupted, when a boat of Afghans crashed ashore as we were about to pass that precise location, the throngs of refugees pouring into the street. One young man took a few paces on European soil, then paused before of our car, raised his hands, thanked G-d for this moment, and collapsed to the asphalt weeping. They made it! Here! Alive! We then continued on our way, with Saraf (the youngest daughter) on my lap in the front seat. She is my new best friend; we met on the side of the road, shared a good cry (gratitude, fear, emotional overload), and then I fed her little bites of banana (which I learned is "mouz" in Farsi) while bouncing her on my knee – dressed in a dry fleece onesie, knit scarf and pink mittens. It was my happiest of moments: able to be present with love and tangible help for the beautiful children who need it most around our world.

The sun was setting (a spectacular sight, in contrast to the catastrophic crisis) as we dropped the family at a transit camp for hot soup and milk upon arrival – and carefully turned the car around, determined to make it off the dangerous, narrow, uneven, winding road before nightfall. Only minutes later, we were flagged down in the middle of the dark coastal stretch. "STOP! PLEASE!” A young Danish man waved his hands frantically to get our car’s attention. “There are only three of us and a boat is coming in!" We slammed on our brakes and ran out of the car, zipping our jackets as we raced across the freezing cold beach. The sun had all but set, as the small rubber dinghy thrashed against the sharp rocks in the choppy waves. Two men ran into the sea to pull the vessel closer, while we waited in knee-high water – soon being tossed babies, children, possessions anything, as we helped to pull the weak and terrified ashore safely. The boat was partially submerged, bags and clothing floating on the surface, as the last few men dug underwater for missing money or electronics; the tragedy of how people literally lost everything and came in drenched to their hips at minimum now became clear to me. In one hand, I was shining a flashlight (the only light) on the boat as refugees poured out and, in the other, holding tight to a six-month-old child. Her mother had thrown her (yes, thrown with airtime) to me before she herself struggled and crawled to shore. The tiny girl was sopping wet, so after ensuring all passengers were accounted for, I took the family to our car for dry clothes. With mother, father, three brothers, and aunt in tow, Jodi and I clothed the kids, provided fresh socks and shoes for all, and offered up what little crackers and lollipops we had on hand. I changed the little one's diaper (my first ever!! See that, momma Judi?!) and dressed her in layers upon layers and a fancy hat to top it all off. We packed them into a passing car, driven by our new friend and fellow renegade volunteer, Tony with dreads from Sweden, and bid them adieu, including ample kisses and “shukrans” (thank yous).

It was pitch pitch black as we began to drive up the hill, covering a few hundred yards before I spotted a faint flashing light down below, at the bottom of the cliff and rapidly approaching the jagged shore. Two women in a car just ahead of us stopped as well (both Americans, the first we have met on the island, and one a member of the Human Rights Watch board). It was clear: another boat was coming – and because of the cliff location, this would be an extraordinarily complicated rescue that required professionals. We phoned a team of Spaniards who are skilled in just that, arriving five minutes later in full wet suits and tying ropes to trees where we determined the boat had crashed below. They hastily descended the 200 plus feet, navigating mud, rocks, and trees – and within minutes began to carry and pass the children up, one by one. The two women and Jodi formed a chain in the final part of the ascent, pulling people up, limb over limb, until handing them to me (braced by my one leg wrapped around a tree) to hoist the final vertical. Somehow, it worked! The babies came first, who I held, sometimes two at a time. Then the young children, weeping hysterically, in frantic search for their parents who were nowhere to be found. Then the parents, who embraced their children as if the separation had lasted years. Then the young able-bodied men, who started to help in the process, some with physical strength and others through basic English, asking questions about water, clothing, food. I had no good answers, which truly broke my heart, and I told them the difficult truths; we had no supplies on site, aside from my basic first aid kit (I went on to wrap up one mangled pinky) and minimal dry clothing and shoes for the littlest ones. BUT I did have hugs – and enthusiastically doled them out en masse with absolute sincerity, which I know was received with genuine emotion by each new arrival. One man asked how no police were there to help them. “We were shouting ‘Please help! Please help! Police! Police!” he said, in disbelief that here – on the shores of glorious, civilized Europe – no authority was there, not even when needed to offer lifesaving assistance. I apologized – on behalf of all of us around the globe who have failed these refugees on too many levels to count for too long, this being just one minor example. He hugged me, “You are good woman.” I cried. He hugged me again. I cried more. I tried to stay strong, but I simply could not – with utter chaos all around me. By then, more had gotten word and arrived on scene. Photographers with long lenses stood at the edge of the cliff, setting off bright flashbulbs in the eyes of refugees who were struggling to make it up alive, yet never offering a hand. Side note: I believe photojournalists play a critical role in disaster zones, for disseminating messages with visuals is an imperative, but there is a time and a place to put your camera away and do the dirty work – and this was one such moment, in my opinion. One doctor came, descending the mountain to help a man who the rescuers believed to be going into cardiac arrest from the stress. Two women arrived with more clothing and diapers for the children, whom they were changing in the trunk of our car by cell phone light. The Spanish rescue team worked miracles, hauling two individuals up by pulley: an elderly man and woman who could not walk, let alone climb a rope up an arduous rock face. I placed the two of them, along with newborns in our car to stay warm. When I sat the old man down in the front seat, he did not let go of my neck, hugging me near and crying into my shoulder; what a moment. I cried, again. By that point, the road was a muddy mess from the water dripping off all of the refugees and their possessions, 57 off the first boat alone (surely designed for no more than 20). Additional people were now coming in; three more boats, to be exact, who had apparently seen our influx of light and followed it to this treacherous spot on the shore. I flagged down every single car that passed, pleading with drivers to take people to the nearby camp, yet few agreed. For those cars (and one pickup) that said yes, as well as the two vans who came to save the day, we packed dozens into each vehicle – too many, though all were delighted to not have to make the hilly, muddy trek in the cold, dark night on foot. Strong young men, like a crew of Eritreans (the first I have seen on Lesvos to date) and a crew of Syrian brothers, set to walking, smiling as they hugged me goodbye – but not before a good number of selfies and photos with moi. “Facebook!” one exclaimed, after giving thumbs-up approval to a picture his friend had taken of us. Boys will be boys, no matter the circumstances! A couple of hours later, we had successfully gotten *almost* every single person out of the boats, up the cliff, and into a vehicle or walking safely on their way – and we thanked all, before collapsing into our car.

That almost relates to one man who had jumped overboard about 10 meters out, hoping to guide his boat safely to the island, but never arrived. His boatmates told the rescue team, who sent someone out to swim for him, though he returned empty-handed after a twenty minute search. I began to weep as we pulled away; a person had died, a human being had been lost at sea, so close to reaching this stepping stone in their dream, and there was absolutely nothing that I could do – or could have done – to change the course of events. I also was in utter shock at what had just transpired: a cliff rescue of helpless refugees fleeing dictatorship and violence on a rather random island in the middle of the night… which sounds unnecessarily dramatic, though is rather factual. How is this real life? And how did I possibly end up here – able to actually contribute in even the most minute of manners?

We forged onwards in our car – exhausted, filthy, and emotionally drained. Only a few bends later, we came upon a fire at the side of the road, where a young boy jumped in front of our path to force us to stop. A boat of Afghan refugees had just come ashore, with no one to greet, help, or direct them… so they had industriously made a blazing fire, burning waterlogged possessions to keep warm. I hopped out. Hello! Welcome! Hugs! And proceeded to call and flag down enough cars and vans to take the whole of their boat to board buses to camp, picking up two Syrians and two Pakistanis (the first I have seen here of that nationality as well) en route. Success. One of my fellow drivers informed me that they had found the missing man at sea and he was blessedly alive and en route to camp, not even needing a hospital immediately. Double (triple, quadruple, quintuple) success.

I feel like I have become something of a welcoming committee – not merely for Lesvos, but for Europe, for the West, for the world at large, for the next chapter in the lives of those arriving on the shores of the island. These refugees have zero clue who I am or where I am from. I could just as easily be a Greek farmer, a European legal authority, a doctor for an international NGO… who knows. But I am just me: an individual who cares deeply, who feels all the feels, who loves greatly, who wants to improve lives however I am able, who desires to better the world through grassroots action, who uses personal experience to push for larger policy that is so desperately needed. Our world cannot afford – morally, societally, legally, economically – to allow this travesty to continue. THIS IS A CRISIS. AND IT MUST CHANGE.

Comments