News Worth Smiling For. Refugees in Lesvos… Day Six.

- erinschrode

- Oct 30, 2015

- 12 min read

I am smiling right now… news worthy of a small celebration, having been solemn and heavyhearted for days, as the weight of the refugee crisis unfolding before my very eyes crushes my spirits. This may be surprising, given that I spent the day in Moria, the detention center-turned-refugee camp now infamous for unbearable, inhumane conditions (if you want to hear about it in its most hellish form, you can read this gut-wrenching article that quotes a recent volunteer on-the-ground). But I choose to smile this evening because of the remarkable hope, indefatigable strength, and unbridled goodness of the individuals I met today (read to the very end for their quotes… and a good cry!). The tears in my eyes as I type right now are ones with a tinge of joy, taking shape amid a thick air of overwhelming sadness.

Moria is located just outside Mytilini, Lesvos’ capital port city, and the location to which all refugees are bussed after making their way from the northern shores to transit camps, about an hour and a half drive. The sight is an appalling one, though conditions are supposedly far better than a few weeks back, due to recent dignitary visits – and I was not there at night, while people freeze due to a shortage of blankets and plastic bags burn, poisoning the shared air, nor in the rain, when lack of shelter prevents refugees from keeping dry and their clothes, skin and feet begin to rot, literally.

Barbed wire and cardboard signs to separate nationalities mark the entrance to the menacing camp: Syrians straight ahead, Afghans and Iraqis to the right. Syrian refugees, as well as the very small numbers from Somalia, Yemen, South Sudan, Palestine, and Eritrea get papers for a six-month suspension of deportation. The fate of those from Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, Pakistan, and Lebanon remains up in the air. There are two entrances for two camps: one for each of the above-noted groups. On the Syrian side, there are two lines, or masses of people, as the case may be: one for single men, one for families. The lines last a minimum of multiple hours and can take days to pass through, forcing people to stand and wait through heat and bitter cold, many who should not be standing at all, often without food or water. As one meal a day is iffy at best (having been shut down entirely a couple of weeks back, I am told), most resorting to buying snacks and finger food from stands on the street just outside the high fences.

“Where should we go?" That was a real question posed to me by two refugees at the entrance to camp today. “Belgium or Germany?" 18-year-old Mustafa and his 29-year-old uncle Muhammad stared and pointed at the laminated partial map of Europe for quite some time. It was marked with colored highlighters, denoting boat lengths and bus routes from Lesvos to Athens, Athens to Macedonia. These two fled Syria, leaving behind their entire family, studies (Mustafa just graduated high school), and career (Muhammad worked in the oil industry, after receiving a two-year college degree) and know not where they are headed beyond tomorrow's ferry to mainland Greece. “Where?!" Mustafa asked again, sincerely desiring our outside opinion on the issue. They inquired about costs of travel, means of transportation, distances, schedules, durations – the great unknown means opportunity, but also tremendous risk, even for two able-bodied young men (one of whom speaks English, a huge asset) without the burden and responsibility of family or children to feed, clothe, carry, and manage.

Another small group approached us as they entered. “Where to? Where do we go?” I apologized sincerely for not being able to answer, as we too had just arrived and were trying to get the lay of the land. But that was not good enough, I decided, so we set out to try to figure out an answer with and for them.

Without the red tape or protocols, hierarchies or toes to step on like most organizations, NGOs, government officials, media, you name it – we have the space to DO, to execute, to go renegade. And we are not yet fatigued, like many working at the camp, mostly ordinary do-gooder volunteers – undertrained, underprepared, understaffed, underequipped… and overwhelmed. We need more people here, now. So if you want to come, COME! The stream of refugees will not cease, though volunteers will diminish in coming weeks and months, as winter sets in and conditions worsen, presenting an even more acute need.

We quickly discovered that there is no one in charge, no one to ask, no rule, no authority, no order. We approached a Greek police officer driving a tank through the property: no idea. A UNHCR administrator leading a family to the other side of the camp: not a clue. A Save the Children worker outside the organization’s packed tent: nothing. The lines were growing longer and the crowds more substantial, so we made our way to the front, where people’s faces were pressed against the chain link fence, eyes fixed on the processing tables on the other side, fingers poking through the small openings. A police officer on the other side beckoned us in, “American? Okay!” and opened the gate, just like that. We told our newfound friends – hundreds of Syrians desperate to know what to do, where to go, why they were waiting – that we would return shortly, courtesy of Adam, a man who had risen to the invaluable role of translator. Lines snaked about the portable buildings inside the closed off area, patient refugees waiting to get processed under strict watch and control of armed police. No one could adequately answer our questions, so one officer referred us to the commander, the number one on site, and wrote his (very long, complicated Greek) name on a slip of paper. We set out to find this man; keep in mind, the camp population numbers in the thousands on quite a sizable piece of land with many fences and structures.

I found myself on one side of a barbed wire-capped fence, a mass of Afghans and Iraqis on the other, being screamed at and threatened by police. So I ran over and asked to pass… the guard heard my English, glanced at my Red Cross ID around my neck (among the most useful certifications I have ever gotten), checked out my sunglasses (surefire sign of a foreigner) and unlocked the gate without pause. I looked up at the fuming officer, “You want them in one row, yes?" He nodded in frustration. “Marhabaa! Saff wahid!” I waved hello and gestured my hands calmly, as I spoke in broken broken Arabic and worked my way through the crowd with genuine hugs and smiles galore, politely moving with people to create the order he needed to hand out bus tickets – the final leg in a long journey to the port to catch the ferry to Athens. My approach worked! I am now even more convinced that love and solidarity are the answers for crowd control, as for most things in life.

We went on to miraculously find and speak with the police chief, who told us the camp protocol I noted above, which had just changed yet again, in their quest to create the most efficient, safe process possible. The key element of his answer: Syrians could register at Moria OR Kara Tepe, a nearby camp which had just been reopened for Syrian families. About 2,500 people can be processed daily at Moria, he said, yet far more than that arrive in each 24-hour period, hence the seemingly endless lines.

We made our way back through camp, past a good number of durable shelter structures and formidable tents. Save the Children is very present, as is Action Aid! and various UN agencies, mainly UNHCR, but primarily (near exclusively) on the Syrian side. The other is in shambles, from what I could see, confirmed by many accounts. People sleep amid mud and garbage, as there are not enough tents, blankets (the single item for which I was asked most) or layers (please hold drives for winter clothes!) to keep warm.

When we returned, the lines of Syrians had some semblance of order. Adam, our self-appointed translator from earlier, said that a few men stepped in to self organize – which had worked, until the gates were opened to let in a few more for processing. The crowd had charged, a stampede which pinned one little boy to the fence and split families, as the entrance was immediately closed off forcefully, likely not to reopen until tomorrow. Alan, another man who spoke perfect English, stepped in to help translate people’s numerous questions. Between Alan, Adam, and Ziad (Adam’s cousin), we were able to offer worthwhile answers to hundreds of rightfully confused souls. But mothers wanted to know more about Kara Tepe, the camp for families. The only way to find out was to go ourselves, so while Adam and Ziad stayed to relay messages, Alan, Jodi, and myself made the short drive to Kara Tepe. We got Alan’s life story, which I recorded and must do something with, but here’s the short of it: he just finished a master’s degree in actuarial mathematics in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia (smart guy!) and returned to Syria, where he was forced to join the army or flee, so he fled, alone. He wants to make it to Norway (via Macedonia, Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, Austria and Germany… whew!) to contribute in a field related to economic statistical predictions, though my lay brain could not entirely comprehend his thorough and specified explanation. Alan’s English is impeccable and his spirit divine; this man is going places and I cannot wait to follow such a bright journey!

The scene at Kara Tepe was a very different one: fewer people, mostly families, but far less shelter and little NGO presence. I heard a mother with five children in tow approach one aid worker, only to be told there was unequivocally no remaining space in which she could sleep and that the limited supply of blankets would be first come, first serve sometime after sundown. People mostly just sat in open spaces, rather than pushing in massive lines. The authorities were indeed processing paperwork for Syrians – both families and singles – but bus and boat ticketing had finished for the day (it was still early afternoon). Alan politely asked if he could join the line. Of course! We were delighted to be able to usher him along in the puzzling process. Jodi and I drove back to Moria to explain that families were welcome at either camp, though made no promises of shorter wait times or better conditions at the other, though it did seem more calm. Adam needed to see a doctor, so we drove him and his cousin Ziad back to Kara Tepe, where we waited in line outside the Medecins Sans Frotieres (Doctors Without Borders) tent until it opened. There was one medical setup for the entirety of the camp, only open from 4 to 11pm… and that is good, in the larger context of inadequate doctor presence for sick, injured, and ill refugees on the island, not to mention pregnant mothers and newborns… so if you are a medical professional considering volunteering, COME!

I stood with Ziad and heard of his life story and unreal journey – while watching kids fill water bottles in the tap (clean running water!) and listening to the occasional bullhorn atop a passing car, blaring the names of missing children (as parents on the only legal guardians, underage kids are separated from relatives early and often). Both he and Adam are Syrian, but were working for American oil-related companies in Iraq before being approached and threatened by ISIS multiple times, forcing them to flee both their country of resident and home country; their tales were unbelievable and rich with everyday detail. Close calls with ISIS is an experience shared by many young men in their twenties (like these two) and thirties, and frequent topic of discussion with us Americans, as all with whom I have spoken agree that the US can and must take decisive action to halt these modern day terrorists. “Now they can help us,” is how Ziad put it diplomatically, in talking about the United States’ responsibility. His university degree is in something engineer-related, but he dreams of being a pilot – to fly the two of us to Tahiti, we decided! He and Adam took a plane to Istanbul, like most, but then began the journey to Greece overland, for which they paid much more. High police presence in the jungle forced their group to the coastline to make the crossing by sea, which Ziad had promised his mother he would not do, due to her fear of the extreme risk. After a failed attempt, which left Adam in the water wedging his body between the boat and rocks to keep from a dangerous crash that would threaten all, and a night freezing on the beach with only two 4x4 tents for the entire group of 40, they were forced into another boat by Turkish smugglers at gun point, another all-too-common shared story of violence. The motor on this burnt out 100 meters from Greek waters, after only a short time at sea. With no captain, the group drifted for hours, luckily making it ashore here in Lesvos at a safe spot with welcoming volunteers. “It was like I won the Olympics!” Adam exclaimed in recounting that magical moment. Ziad was in a state of shock and immense gratitude, praising the higher beings. I am not a praying person, but this woman has prayed more in the past week than in any I can remember; I cannot not, when miracles are so urgently needed in these against-all-odds circumstances.

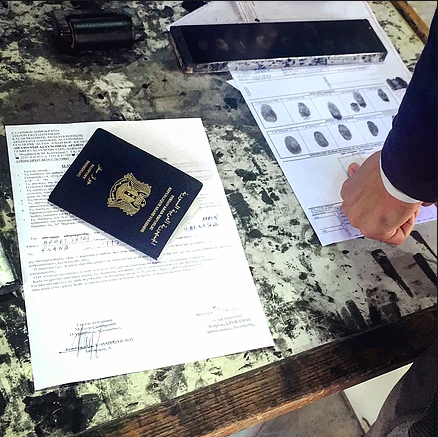

We went on to talk for hours; Ziad is extraordinary – and taught me so much, thanks to the lack of language barrier, as was the case with Alan’s fluency, both of whom I was lucky enough to cross paths with at the camps. I have met thousands upon thousands of refugees in the past week – remarkable souls with whom I have shared unforgettable moments, stories and emotions. I have spoken personally with hundreds, learning of their journeys and backgrounds. And today, I realized just how small the world really is. While speaking with Ziad amid the masses, a young man came over and politely asked a question about hospital discharge papers – in proper British English. His name was Firas and he explained that he had been hospitalized for two days, unsure if I had heard about the shipwreck. I hugged him tightly and said, of course, that I had been there at the docks to help as the coastguard brought them in from sea – and was utterly delighted to see that he was doing so well. He went on to say that he would be in the hospital with his uncle through the weekend because the man was "too big to move." That could be only one person, I thought: Okba. I had lay my body next to his uncle's in the chaos following the coastguard rescue to warm his frigid physical self and we had gone on to speak for two plus hours. I knew the entire story of his Syrian family! “You are THAT girl!” Firas said that his uncle shared our tale. We cried in a wholehearted embrace! I escorted Firas through the processing lines to get the almighty paper which allows for passage to and through mainland Europe – and did the same for Ziad and Adam, neither of whom had passports, as they had been lost with their bags and all other possessions at sea. Not having any form of identification (the case for many refugees) did not prove a problem, thanks to the humanity and diligence of a Greek police officer. There are ways to make this system work for people – and today I was proud to see that in action. Ziad called his mother from line, putting me on the phone for a brief moment. “Take care of my son, my loveliest son,” she said through tears of gratitude, as we went on to sing his praises! I have no doubts that they will not only survive, but thrive.

We left the guys, after exchanging numbers with promises of WhatsApps soon, and offered Firas a lift into town, toward the hospital. I inquired as to how his English was flawless – and he explained that he had worked as fixer in Istanbul for BBC and ABC. When I think journalism and the Middle East, I think Molly Hunter, a dear friend and ABC news reporter who I have known since age five. On a whim, I asked if he knew her. “I love Molly. I was going to tell you when we met that your remind me of my friend. But I stopped.” Smallest world ever! People always thought we were sisters growing up, and still do. I could not believe that there, in the middle of such darkness, I met one refugee – on an island that has seen 350,000 pass through – who knows and has personally worked with one of my oldest friends. The universe has a plan, I tell you! With that, we dropped him at a cell phone store to replace his iPhone, lost in the shipwreck, then headed to the car rental place to pick up a second vehicle and make the long drive home from Mytilini to the north of the island. Half way through my ride, I got a text from Molly: “You met our fixer Firas!!! He told me!! He is amazing."

For some reason, today felt different. Maybe it is because I have become desensitized to the horrific conditions all around me, which I very much hope is not the case, but maybe it is because of meaningful, in-depth conversations with peers I really really like. It is easy to cast off refugees as just that, refugees – and therein forget the humanity, the parity, the common ground. I never place myself above anyone, least of all these brave individuals, but there is a certain distance – and in that divide, a narrative of misery can be written. The fact that I do not speak Arabic or Farsi – or Dari or Pashtu or Urdu either – means that many opportunities pass me by to talk about life and ask a million-and-one questions, as I do openly without shame. Conversation yields understanding, which helps me to better make sense of this tragic situation, though does not make it any easier. While my discoveries today were far from pleasant – camp squalor, failing systems, grave realities of ISIS, violent sea crossings – these people are beyond extraordinary. I believe in them with every ounce of my being! There is hope, truly.

I received two texts from my new friends that lifted my spirits. I wish to share these raw snippets because they made my heart profoundly happy, NOT to be self-congratulatory in the slightest. I hope that these words underline the power of showing up, of loving, of presence, of doing simply because you can. Impacting one life is a gift beyond measure – and you will never know what even the tiniest of gestures can mean to another now and evermore.

“I swear, you are an amazing person. Stay like this cuz [ull] always feel like ur human. Doing the right things. I will never forget what uve done to us today. Keep going.”

"Erin thanks for offering support. Yesterday I was completely overwhelmed with the unconditional love and help from u guys. I felt humbled. I start [to] think would i do same if we where to switch positions. U guys are heros. Will always remember how two lovely american ladies taught me the real meaning of humanity."

Comments